Arnold Palmer, the champion golfer whose to the max style of play, exciting competition triumphs and attractive identity propelled an American golf blast, pulled in a taking after known as Arnie's Army and made him a standout amongst the most prominent competitors on the planet, passed on Sunday, as per a representative for his business undertakings. Palmer was 87.

The representative, Doc Giffin, said the reason for death was complexities from heart issues. Paul Wood, a representative for the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, affirmed that Palmer kicked the bucket Sunday evening at UPMC Shadyside Hospital in Pittsburgh.

From 1958 through 1964, Palmer was the appalling face of expert golf and one of its prevailing players. In those seven seasons, he won seven noteworthy titles: four Masters, one United States Open, and two British Opens. With 62 triumphs on the PGA Tour, he positions fifth, behind Sam Snead, Tiger Woods, Jack Nicklaus and Ben Hogan. He won 93 competitions around the world, including the 1954 United States Amateur.

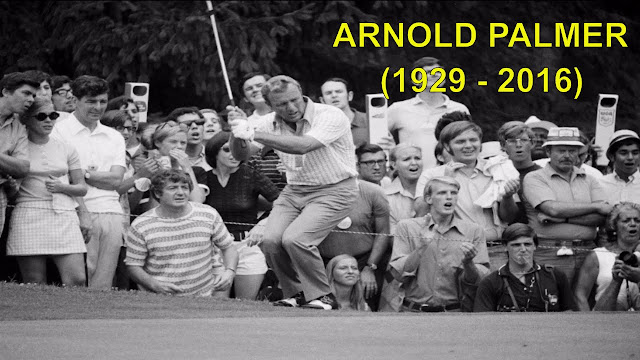

In any case, it was more than his scoring and shotmaking that spellbound the games world. It was the manner in which he played. He didn't so much explore a course as assault it. On the off chance that his swing was not exemplary, it was brutal: He appeared to toss every one of the 185 pounds of his solid 5-foot-10 body at the ball. In the event that he didn't win, he at any rate lost with style.

Nice looking and beguiling, his graying hair falling over his temple, his shirttail fluttering, a cigarette now and then dangling from his lips, Palmer would walk down a fairway recognizing his armed force of fans with a sunny grin and a raised club, "similar to Sir Lancelot in the midst of the large number in Camelot," Ira Berkow wrote in The New York Times.

Furthermore, the TV cameras took after along. As Woods would accomplish over 30 years after the fact, Palmer, a child of a golf professional at Latrobe Country Club in the steel town of Latrobe, Pa., verging on without any assistance invigorated TV scope of golf, enlarging the diversion's prevalence among an after war era of World War II veterans getting a charge out of monetary blast times and a sprawling green the suburbs.

His praised contention with Nicklaus and another champion, the South African Gary Player — they got to be known as the Big Three — just added to Palmer's allure, and usually, he, not the others, had the exhibitions on his side.

"Arnold promoted the diversion," Nicklaus said. "He gave it a jolt when the amusement required it."

Ascending to the Moment

Hitching up his jeans as he walked down the fairways or before arranging a critical putt, Palmer put "charge" into golf's vocabulary in 1960. In the last round of that year's Masters, he birdied the seventeenth and eighteenth gaps to win by one stroke. After two months, in the United States Open at Cherry Hills, close Denver, he shot a last cycle 65 to win by two over Nicklaus.

"I appear to play my best in a major competition," Palmer said. "First off, my diversion is better adjusted to the harder courses. For another, I can get myself more keyed up when a vital title is in question. I like rivalry — rugged should, as much as possible."

Also, in the event that he lost, his armed force did not abandon him. In the 1961 Los Angeles Open at Rancho Park, he recorded a 12 on the standard 5 ninth gap when he hit four balls outside the allotted boundaries. Palmer's fans were flattened, similar to him, however, some way or another, his flubs improved his allure. He was human; he could blow a lead or a shot like any duffer. What's more, they loved that he went down swinging, with his rushing, put it all on the line play. In the event that he hit a wayward tee shot to a clumsy spot, he, for the most part, went for the green, as opposed to chip the ball securely back to the fairway, as different golfers would have done.

"You can commit errors when you're being a traditionalist, so why not go for the opening?" he said. "I generally feel like I'm going to win. So I don't feel I'm betting on a considerable measure of shots that make other individuals feel I am."

His epithet among visit masters was the King, in spite of the fact that he never lounged in the title. In any case, it fit. He was the main competitor to get three of the United States' nonmilitary personnel respects: the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Gold Medal, and the National Sports Award. Furthermore, he turned into a small time multimillion-dollar combination.

As the president of Arnold Palmer Enterprises, he regulated the configuration and improvement of more than 300 new or renovated greens around the world, and additionally golf clubs and garments.

He advanced a beverage known as the Arnold Palmer, a blend of frosted tea and lemonade now sold under his name on store racks.

He was a noteworthy asset raiser for the Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children and Women in Orlando, Fla., and for Latrobe Hospital. He was the first director of digital TV's Golf Channel and was a long-term corporate representative, strikingly in a Pennzoil business including a tractor he had driven experiencing childhood with the Latrobe course.

Subsequent to purchasing his first plane, a utilized twin-prop Aero Commander, for $27,000 in 1962, he turned into the main golf ace to pilot his own particular plane from competition to competition. He graduated to planes in 1966. The Latrobe air terminal is named for him.

With two co-pilots and an eyewitness, he circumnavigated the globe in 1976 in 57 hours 25 minutes 42 seconds, a world record for planes in the 17,600-to-26,400-pound classification. He spent over 20,000 hours in the cockpit.

Keep perusing the principle story

RELATED COVERAGE

The Arnold Palmer: Two Parts Iced Tea, One Part Lemonade SEPT. 26, 2016

Q and An/ARNOLD PALMER

Drawing nearer the Economy With Optimism MARCH 28, 2009

Games OF THE TIMES

A Show of Force for Arnie's Army at Augusta's First Tee APRIL 5, 2007

Games OF THE TIMES

50 Years Ago, Arnold Palmer Let the U.S. Open Slip Away JUNE 16, 2012

Television SPORTS

In 3-Hour Show on Palmer, Golf Channel Joins His Army APRIL 12, 2014

Late COMMENTS

He drove the principal all-volunteer power in this nation much sooner than the draft finished. We were all individuals from Arnie's Army. Presently he can demonstrate the...

Tom Rooney 34 minutes prior

Most everybody in Pittsburgh would have an Arnold story since he was consistent with his underlying foundations and was unmistakable pulling for the Steelers, raising...

I never saw Mr. Palmer without a grin all over and without a kind word for his fans. This remained constant in his later years when his wellbeing...

"Flying has been one of the colossal things throughout my life," he said. "It's taken me to the most distant corners of the world. I met a huge number of individuals I generally wouldn't have met. Furthermore, I even got the opportunity to play a little golf en route."

He was a section proprietor of the Pebble Beach Resort in California and important proprietor of the Bay Hill Club and Lodge in Orlando, the site of the yearly Arnold Palmer Invitational competition on the PGA Tour. Consistent with his underlying foundations, he made his essential home in Latrobe, however, he spent winters at Bay Hill.

His handshake concurrence with Mark McCormack, a Cleveland legal counselor he met amid a three-year spell in the Coast Guard, prompted McCormack's framing the International Management Group, now the world's first games organization. Palmer was its chief customer.

One of Palmer's mistake was that he never won the P.G.A. Title to finish a profession Grand Slam — titles at the four noteworthy competitions. That disappointment particularly hurt since his dad, the Latrobe Country Club professional, was a P.G.A. part who had shown him the diversion.

"I ought to have won it two or three times," Palmer said. "I needed it too terrible. Everybody was calling it to my consideration."

Extreme Losses With Triumphs

Palmer contended in the top positions of a requesting, demanding diversion against some of the history's most noteworthy players, so heartbreakers were presumably inescapable.

At the 1961 Masters, Palmer required just a standard 4 on the eighteenth gap to wind up the primary golfer to win at Augusta National in back to back years. Be that as it may, after a decent drive, he slid his 7-iron methodology into a dugout, impacted out over the green, chipped 15 feet past the container and two-putted for a twofold intruder 6 to lose by a stroke to Player.

Palmer additionally lost three 18-gap United States Open playoffs — in 1962 to Nicklaus at Oakmont, close Pittsburgh (it was Nicklaus' first significant triumph); in 1963 to Julius Boros at the Country Club in Brookline, Mass.; and, in an especially pounding route, in 1966 to Billy Casper at the Olympic Club in San Francisco, after he had driven Casper by an apparently unrealistic seven strokes with nine holes to go in the last round.

Palmer was, in any case, the PGA Tour's driving cash victor in 1958, 1960, 1962 and 1963 and its player of the year in 1960 and 1962. In 1968, he turned into the main golfer to procure more than $1 million in profession prize cash on the PGA Tour. The honor for the main cash victor every year is presently named for him. He was voted The Associated Press' competitor of the decade for the 1960s.

Palmer was 77 when he played his last focused round, on Oct. 30, 2006, at the Administaff Small Business Classic in Spring, Tex., on the Champions Tour. Subsequent to hitting two balls into the water on the fourth gap, he pulled back with a sore lower back, in spite of the fact that he completed his round — without keeping track of who's winning — in light of the fact that he owed it to his fans, he said.

"The general population, they all need to see a decent shot," he said, "and you know it, and you can't give them that great shot. That is the point at which now is the ideal time."

Arnold Daniel Palmer was conceived in Latrobe, southeast of Pittsburgh, on Sept. 10, 1929, the main offspring of Mildred and Doris Palmer. (A sister, Lois Jean, who was known as Cheech, was conceived when Arnold was 2.) His dad, who was known as Deacon, then Deke, worked in the steel factories and as a worker and greenskeeper at the Latrobe club, then a nine-gap course, until 1932 or '33, when he was named the club star. Arnold's mom kept the master shop books. The family lived in a humble house on the edge of the course.

Arnold was around 3 when he started to swing a 3-iron with a sawed-off shaft. His dad let him know, "Hit it hard," and he did. At age 9, he shot a 45 for nine holes. He went ahead to win the Western Pennsylvania Junior three times and the Western Pennsylvania Amateur five times before he entered Wake Forest, subsequent to moving on from Latrobe High School. In school, he played on two Atlantic Coast Conference title groups.

"I don't think I have any more grounded nerves than the following man," he once said. "I assume it's simply the persistence I got from my mom, Doris, and the ornery cantankerousness I got from Pap."

His association with his dad ran profound, and Palmer would become passionate in reviewing him. Deke Palmer had polio as a kid and strolled with a limp, and in 2014 the P.G.A. of America made him the primary beneficiary of an honor set up in his honor, referring to a P.G.A. part who had defeat individual misfortune to add to the diversion. He passed on of a heart assault at 71 in 1976 subsequent to playing 27 gaps at Bay Hill.

As a Wake Forest understudy, Palmer was broken by the passing of his cohort and dear companion Bud Worsham, the child of the 1947 United States Open champion, Lew Worsham, in a car collision. Palmer soon pulled back from school amid his senior year and served three years in the Coast Guard. After his release, he was filling in as a businessperson in Cleveland (where he met McCormack) when he won the 1954 United States Amateur at the Country Club of Detroit.

Fast Proposal, Long Marriage

At an eastern Pennsylvania tournament a few weeks later, Palmer met Winifred Walzer, a 19-year-old who was studying interior design at Pembroke College, an arm of Brown University, in Providence, R.I. Her father was an institutional food distributor in Bethlehem, Pa. She and Palmer hit it off at dinner the next evening, and he proposed to her three days later.

After eloping, they were married in Falls Church, Va., before a small group of Palmer family members and friends on Dec. 20, 1954. (The Walters stayed away, convinced that their daughter had made a mistake.) The couple traveled the 1955 pro tour in a secondhand trailer.

“For years,” McCormack said, “Winnie handled the family finances and handled them well while heeding certain rules set down by Arnold, whose ideas about money do not follow common practice. She balanced the books, paid the bills, made the travel arrangements, mailed the entry blanks and, in short, devoted her entire attention to one goal: making sure that her husband’s mind was free to concentrate on golf.”

On her husband’s 37th birthday, in 1966, Winnie Palmer arranged for one of Arnold’s special friends to attend the family party in Latrobe as a surprise guest — former President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Arnold and the president had occasionally played golf together at Augusta National, where the president, an avid golfer, was a member.

Winnie Palmer died of breast cancer in 1999 at 65. Arnold Palmer married Kathleen Gawthorp, a Californian known as Kit, in 2005 in Oahu, Hawaii. It was her second marriage as well.

She survives him, along with two daughters, Peggy Wears and Amy Saunders; two sisters, Lois Jean Tilley and Sandra Sarni, both of Latrobe; a brother, Jerry, a former general manager at Latrobe Country Club; six grandchildren, including Sam Saunders, a pro who has played in several tour events; and several great-grandchildren.

Conquering Augusta National

As a tour rookie, Palmer won the 1955 Canadian Open. He won twice in 1956 and four times in 1957 before earning the green jacket at the 1958 Masters after a controversial ruling. He was leading by one stroke when his tee shot on the 12th hole plugged behind the green. His request for a free drop was refused. Waiting for a ruling on his appeal, he played a provisional ball (for a par 3) and the original ball (for a double-bogey 5).

Two holes later, his appeal was allowed; his provisional ball for a 3 counted. He won by one stroke over Ken Venturi.

“My first Master's win was the toughest and also the most significant,” Palmer said. “The business with the ruling made winning the tournament as hard as anything I’ve ever done, because I wanted to win so badly and because of my feelings for the Masters.”

It was during the 1960 Masters that the name Arnie’s Army was born. Palmer was on his way to victory with a 30-foot birdie putt on the 17th and a 6-foot birdie putt at the 18th when an “Arnie’s Army” sign appeared on the scoreboard.

“Some soldiers at Fort Gordon were acting as gallery marshals,” Palmer said later, alluding to the sign, “and a sportswriter picked up on their excitement.”

Two months later, at the United States Open at Cherry Hills, Palmer trailed the third-round leader, Mike Souchak, by seven shots as he ate a hamburger in the locker room before the final round. In those years, the Open had a 36-hole finish on Saturday, and when Palmer saw Bob Drum, the golf writer for The Pittsburgh Press, he had a question.

“Silence is louder than

any noise on a golf course

— the deathly silence

that I sometimes feel and

hear when I’m out there.”

MR. PALMERany noise on a golf course

— the deathly silence

that I sometimes feel and

hear when I’m out there.”

“What would a 65 this afternoon do?” he asked.

“For you, nothing,” Drum said. “You’re too far behind.”

“But a 65 gives me 280, and 280 wins the Open.”

Palmer was so angry at Drum, he never finished that hamburger. He went out and drove the first green on what was then a downhill 346-yard hole, then two-putted for a birdie. He also birdied the next three holes, then the sixth and the seventh. He bogeyed the eighth but parred the ninth for a 30 going out, then played the back nine in 35 for a 65 that won that Open by two strokes over Nicklaus, a 20-year-old amateur at the time.

Having won both the Masters and the United States Open, Palmer entered the British Open at St. Andrews, Scotland, hoping to extend his bid for an unprecedented Grand Slam of the four majors in the same year.

‘The Strength of the Gallery’

Despite a 68 in the last round, Palmer lost that British Open by one stroke to Kel Nagle, an Australian. But he won the British Open in each of the next two years, at Royal Birkdale in England in 1961 and at Royal Troon in Scotland in 1962.

In the 1962 Masters, Palmer trailed by two strokes with three holes remaining, but birdies at the 16th and 17th forced an 18-hole playoff with Player and Dow Finsterwald. After a 38 on the front nine of the playoff, Palmer birdied the 10th, 12th, 13th and 14th holes for a 68 as Player shot 71 and Finsterwald 77. In 1964, Palmer won the Masters by six strokes as Nicklaus and Dave Marr tied for second.

“This was my most satisfying Masters,” Palmer said. “I held the Masters in awe when I was young, and I hold it in awe now.”

That Masters title was his last victory in a major, but he won on the PGA Tour as for late as 1973, at the Bob Hope Desert Classic. After he turned 50 in 1979, his mere presence on the Senior PGA Tour, then just formed, helped popularize it while lifting his total prize money on both tours to more than $3.5 million. Even when he struggled on the Senior PGA Tour after surgery for prostate cancer in 1998, his galleries were often the largest, just as they had been four decades earlier.

“I feel the strength of the gallery, especially on a critical shot,” he said in his prime. “Silence is louder than any noise on a golf course — the deathly silence that I sometimes feel and hear when I’m out there. That will tell you how powerful the galleries really are. They have an appreciation of what you’re going through, of what’s happening, and they understand.”

He had a shelf full of honors, and then some. He won the Vardon Trophy for a lowest average score on the PGA Tour in 1961, 1962, 1964 and 1967. He was a member of six United States Ryder Cup teams; he was twice the captain, in 1963 and 1975. He was the Presidents Cup team captain in 1996. He was on six victorious World Cup teams, four with Nicklaus as his partner and two with Snead.

Palmer is a member of the World Golf Hall of Fame in St. Augustine, Fla.; the P.G.A. of America Hall of Fame; and the American Golf Hall of Fame. He also won 10 Senior PGA Tour events, including the 1981 United States Senior Open and two Senior P.G.A. Championships. President George W. Bush presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in a White House ceremony in 2004.

But perhaps no pro golfer enjoyed the simple pleasure of playing the game as much as Palmer did. Including friendly matches and tournaments, he estimated at age 70 that he had played 260 rounds a year. And even though he was hardly the Arnold Palmer who won those seven majors over seven seasons, he still identified with the galleries.

“I did that naturally,” he once said, “because my father told me, ‘Those people in the gallery are all the same as you.’”